In the assembly held on April 14, 1878, Cav. Maestro Ettore De-Champs, Resident Academician, answered that a study of harmony, as well as of languages, that begins from the theoretical side is detrimental and cannot result in authentic command of the subject. More importantly, said De-Champs, the Neapolitan masters introduced the students to the principles of tonality not in rational terms but rather through a gradual refinement of the ear:

It is a common belief today that practice cannot, and ought not, have any other purpose than to confirm those principles that can be apprehended only from theory [ . . . ] but the ancients thought otherwise. Specifically, we all know that the Neapolitan school, where for a long time a system of teaching was used that was opposed to those fashionable today, produced theorists and practical musicians of great value [. . . . ] Up to a few years ago, in almost all schools of music in Italy, harmony was taught more or less in the following way. Just after having learned the intervals, one studied the Rule of the Octave, and practiced it into the three different positions until having attained proficiency. Afterwards one went on to the study of partimento, with little or no care—at least in the first stages—for knowing the origins and tendencies of chords. These origins and tendencies, step after step, became clear as we progressed through the study, with the guidance—besides one’s own talent—of the Master’s personal teaching, and through the reading of the harmony treatises we were asked to consult.

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento : History, Theory, and Practice, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gettysburg/detail.action?docID=916050.

Created from gettysburg on 2020-09-13 11:07:29.

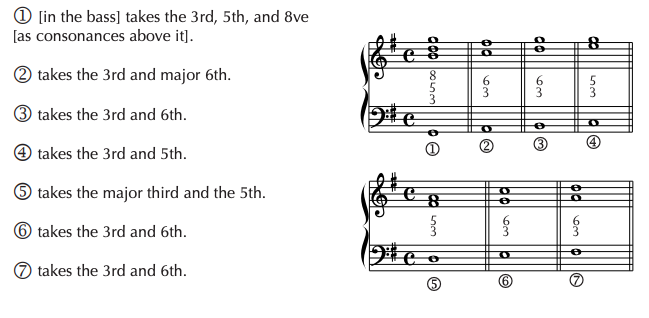

The Rule of the Octave (RO) was a way to quickly add voices to an ascending or descending bass that spans an entire scale. Fedele Fenaroli starts his rules book (1775) with the following:

This allows for a complete ascending rule of the octave:

Note that scale degrees ① and ⑤ in the bass are both 5/3 and all the other bass notes are 6/3. ①

When Fenaroli introduces the actual RO, he uses a larger number of voices (four or sometimes five).

- Scale degree ① stays 5/3

- Scale degree ② was 6/3 and is now 6/4/3

- Scale degree ③ stays 6/3

- Scale degree ④ was 6/3 and now is 6/5/3

- Scale degree ⑤ stays 5/3

- Scale degree ⑥ stays 6/3

- Scale degree ⑦ was 6/3 and now is 6/5/3

- Scale degree ⑧ stays 5/3

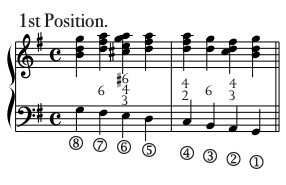

Fenaroli’s descending Rule is:

- Scale degree ⑧ stays 5/3

- Scale degree ⑦ stays 6/3

- Scale degree ⑥ is now 6/4/3 (since it is the ② of ⑤)

- Scale degree ⑤ stays 5/3

- Scale degree ④ is now 4/2(!)

- Scale degree ③ stays 6/3

- Scale degree ② is now 6/4/3

- Scale degree ① stays 5/3

We will practice the rule of the octave in both three parts and four parts beginning with G Major. We will use the voice leading offered by Derek Remeš in his compendium:

Practice these here.